NEW ORLEANS: Twenty years ago, Hurricane Katrina permanently altered the educational landscape in New Orleans. After being completely devastated, the educational system underwent a complete transformation, becoming the nation’s first and only all-charter school district.

The Associated Press asked three survivors to consider what it was like to be a teacher or a student at that turbulent time in advance of the storm’s anniversary.

Suggested Videos

Some were encouraged to become teachers by the relationships they formed with educators who supported them during the crisis. Teachers and schools now experiencing natural disasters can learn from their experiences as well.

The following is a shortened version of the educators’ personal accounts for publishing.

In Texas, a storm evacuee discovered compassionate teachers.

1. When Katrina struck, Chris Dier, a history teacher at New Orleans’ Benjamin Franklin High School, was just beginning his final year of high school in nearby Chalmette. He first sought refuge at a hotel before moving to a shelter for Katrina evacuees in Texas.

1. When Katrina struck, Chris Dier, a history teacher at New Orleans’ Benjamin Franklin High School, was just beginning his final year of high school in nearby Chalmette. He first sought refuge at a hotel before moving to a shelter for Katrina evacuees in Texas.

My Aunt Tina was hammering on the motel door when I woke up. She claimed that the levees had broken and that there were hundreds of bodies all over the place. I will always remember the tap on the door, which informed me that everything was different and that everything had changed.

In order to give us a place to live, an elderly couple who visited the shelter and spoke with us offered us their trailer. We spent the rest of the year in that trailer, and I graduated from Henderson High School in Texas.

These instructors’ treatment of us throughout our darkest moments was one of the reasons I decided to become a teacher. I recall Coach Propes, the soccer coach who provided us with soccer cleats and otherwise looked after us. The English teacher who had us in her class and prepared all the materials is Mrs. Rains, as I recall. I recall the Spanish instructor, Ms. Pellon, who also provided us with resources. I missed weeks of school, so Mr. McGinnis would come in early to educate me in chemistry.

They welcomed me. They gave me a sense of acceptance. They gave me the impression that I was more than simply a number and that I belonged to a greater community.

Growing up, I watched how much time and effort my mother put into her work as a teacher, so it was the last thing I wanted to do. She would use her right hand to grade papers and her left hand to cook. I had higher expectations for my life. However, because I witnessed these professors’ reactions, Katrina altered me in that way.

We discuss everything both before and after Katrina. I currently have both before and after COVID. I immediately became aware of the similarities on March 16, 2020, the day the schools were shut down. After we evacuated during Hurricane Katrina, I had the same questions as the students did. I recall asking myself, “Are we really never going to return to school?”

That weekend, I returned home and penned a letter to elders, providing guidance and support. I wrote about the experience of losing a senior year. People will minimize the problem, I added, since they have no idea what it’s like to have your senior year taken away. However, I am aware. I make an effort to let kids know that their teachers are not forgetting them. They are important to us.

A student missed the affection and care of New Orleans after switching schools.

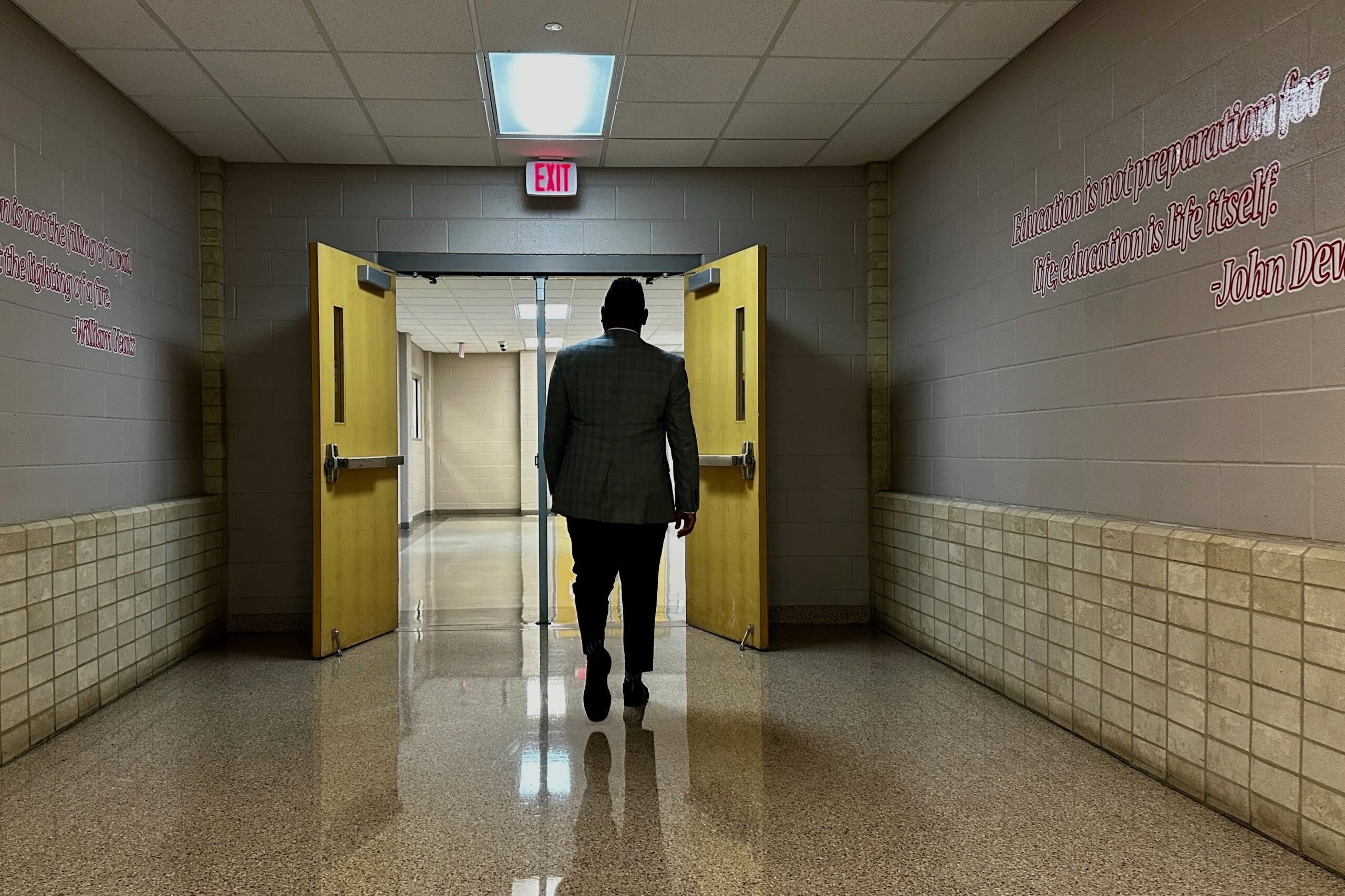

2. Jahquille Ross, who currently works for the education group New Schools for New Orleans, was a principal and elementary school teacher. He attended Edna Karr Magnet School on New Orleans’ West Bank in the eighth grade when Katrina struck.

2. Jahquille Ross, who currently works for the education group New Schools for New Orleans, was a principal and elementary school teacher. He attended Edna Karr Magnet School on New Orleans’ West Bank in the eighth grade when Katrina struck.

After watching the news on Friday, we made the decision to depart on Saturday. I simply recall spending all of my time on the freeway. Forever, literally. During that time, I lived with my brother and sister-in-law because my mother had died in 2003 when I was twelve years old. We were on our way to my sister-in-law’s hometown of Alexandria. I simply recall feeling hungry for a while.

Seeing all that was happening in New Orleans on national television during this period was heartbreaking. You thought, “Oh, we’re going to be in Alexandria for a while,” when you saw the sheer number of people, the effects of the water and flooding, and the destruction caused by the wind.

I thought, “Maybe another week or two,” at that point. That wasn’t the case, either.

In one year, there were one, two, three, and four schools. Wearying out. Everywhere I went, it was difficult to make friends because I didn’t know how long we would be in a given situation. Some places simply don’t have the vibe of New Orleans.

For almost six months, we relocated to Plano, Texas. Very pleasant people and a lovely place. At school, there were more white people than I had ever seen. I became slightly more aware of the racism. Students were more likely to have it.

My academic performance had fallen short of what it had been in New Orleans. It was difficult just to keep up with my coursework. The instructors weren’t really proactive. They were strictly, like, This is the lesson, this is the material, this is when the test is. I just didn t get the love and attention that I was accustomed to in New Orleans.

I came back to New Orleans in March or April. It felt good to be back home. I had my friend base from middle school. I had friends from elementary school. I was back amongst family and elders, like my grandma, my auntie, my cousins, everybody. We lived 10, 15 minutes within each other, which is really good. We had neighborhood-based schooling, you know, prior to Katrina.

It changed the trajectory of my life. I did not want to always become an educator. With my mother passing away, it was school that grounded me. It was the teachers and leaders inside of those school buildings that supported me, pushed me and encouraged me.

I had some pivotal educators in my life who played a big role in my education and my journey. In return, I felt like I could do that for other children of New Orleans. I chose to go into elementary education, so that students in their early years of education would have the opportunity to be educated by a Black male.

Flooding wiped out schools and memories

3. Michelle Garnett was an educator in New Orleans for 33 years, mostly in kindergarten and pre-K, before retiring in 2022. She was teaching kindergarten at Parkview Elementary in New Orleans when Katrina hit and had to evacuate to Baton Rouge.

3. Michelle Garnett was an educator in New Orleans for 33 years, mostly in kindergarten and pre-K, before retiring in 2022. She was teaching kindergarten at Parkview Elementary in New Orleans when Katrina hit and had to evacuate to Baton Rouge.

When we were able to come back to the city, going back to my original school, Parkview, it was devastating to see the school just completely destroyed. That memory, I wouldn t want to go through that again if I could be spared of that.

My mother was a classroom teacher, and she had given me a lot of things. Just memories that you just can t get back. My mother was a little bit of an artist, so she drew a lot of the storybook characters for me. My dad also gave me a cassette tape with the song Knowledge is Power that I used to play for my kids. I lost the tape that he had given me. So, you know, sentimental things. Everybody in the city lost a lot.

My classroom was just molded and water warped, and it smelled, and it was just horrific. I can say, nobody could salvage anything from that particular school. It was just all all was lost.

We were all in Baton Rouge together as a family, 23 of us strong in my daughter s house. Siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles. On top of the 23 people in my daughter s house, she was eight months pregnant at the time. But we were happy. Everybody was safe, and we had to accept things that we couldn t change.

I loved what I did. Got into it strictly by necessity. My second daughter, who is now deceased, had a very rare form of muscular dystrophy. Orleans Parish hired me as my own child s specific aide. She was only in school a short time from December to May, and the next month, two days after her sixth birthday, she passed. I was asked to continue work as a child-specific aide. During that process is when I got the passion and desire to go back to school, to be certified in education.

We think we choose a path for ourselves, and God puts us in the place where he wants us to be. Teaching is where I needed to be. And I absolutely enjoyed it.

___

The Associated Press education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP sstandardsfor working with philanthropies, alistof supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.